Michael Swanton and Elizabeth (Bessie) Bradfield Swanton were my great great grandparents. They were married on February 24, 1843 in the Roman Catholic Church Murragh in County Cork. Their marriage witnesses were John Swanton and Anne Hurley. Bessie’s parents were Michael and Martha Bradfield of Killowen, County Cork.

Bessie’s father, Michael Bradfield was born in 1786. He was a farmer and my great great great grandfather. Michael Bradfield died on May 29,1866 at the age of 80 at his farm in Killowen. The cause of his death was shock caused by a severe fall.

There is a family cemetery on the Bradfield farm, but the stones have been worn smooth by time, and no writing is discernible on them. This may be where Michael and Martha Bradfield are buried. There is also a Bradfield family plot in the old Murragh cemetery.

The James Bradfield for whom this stone was erected was born in 1763. Michael's parents were Richard Bradfield and Susanna Wren (married 1775). This James was most likely Michael's brother.

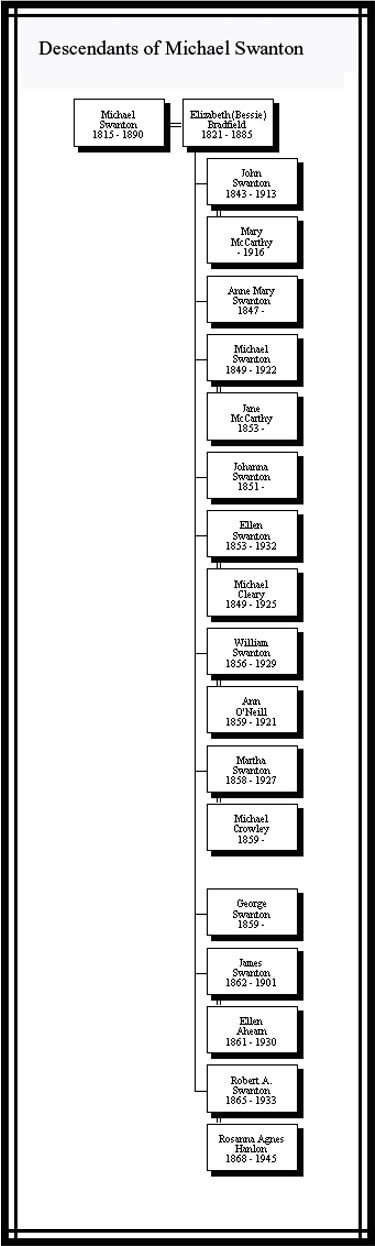

In 1852, Michael Swanton lived in Derrigra, which was part of the town of Ballineen in the parish of Ballymoney, County Cork. Michael Swanton later moved to the townland of Boulteen in the parish of Desertserges, where he was the local pound keeper at Boulteen Cross Roads. The job of a pound keeper was to impound trespassing animals. Michael Swanton was also a carpenter. This area was renowned for its poteen, a potent drink distilled from potatoes and sugar, and I suspect that Michael may have had a fair amount of skill in its making, as well.

According to legend, poteen has been produced in Ireland since the first potato was harvested. The term 'Irish moonshine whiskey' has been in use from around 1660. A levy was then introduced on the legal distillation of spirits carried out privately and unless the operator was licensed by the State, it would be deemed an illegal act and therefore a criminal offence. Not surprisingly a substantial element of the Irish population were elevated to the 'criminal classes' overnight!

Boulteen is a small townland of 212 acres , and was located next to the manor house of Mount Beamish. In 1823, William Daunt, Dr. John Beamish, Florence Carthy, John Buttimer, John Regan and John Cummins lived in Boulteen.

In 1864, the occupants of the townland of Boulteen were:

In the 1800’s, a fair used to be held at the Boulteen Cross Roads every year in June. I visited the Boulteen Cross Roads in 1998, and again in 2001. They were simply two intersecting grass roads with swinging iron fences on the road to Bandon and points west. No houses remained, although I found some stone ruins that appeared to be from old houses.

Although the tenants changed quite a bit from 1867-1870, Michael Swanton continued to rent the same property. He rented first from Thomas Baldwin, then from Thomas Bennett, and later from Mary Moore, a descendant of the Joseph Moore who had rented the property at 1a in 1864.

In 2001, the site of the pound that Michael Swanton rented was covered with a tangle of vegetation. The owner of the land in 2001 (Tim) told me that it is said that many people died there during the famine, and that he was never going to clear that area. He told me that if I came back and found the area cleared, then I'd know he was dead.

On October 20,1877, an M. Swanton of Dunmanway contributed 2 pence, 6 shillings toward a fund for the widow of John Hayes of Ballincorriga, who had contracted fever while attending to his sick wife, and died, leaving 9 children . The M. Swanton who contributed to this fund may have been my great great grandfather, Michael Swanton.

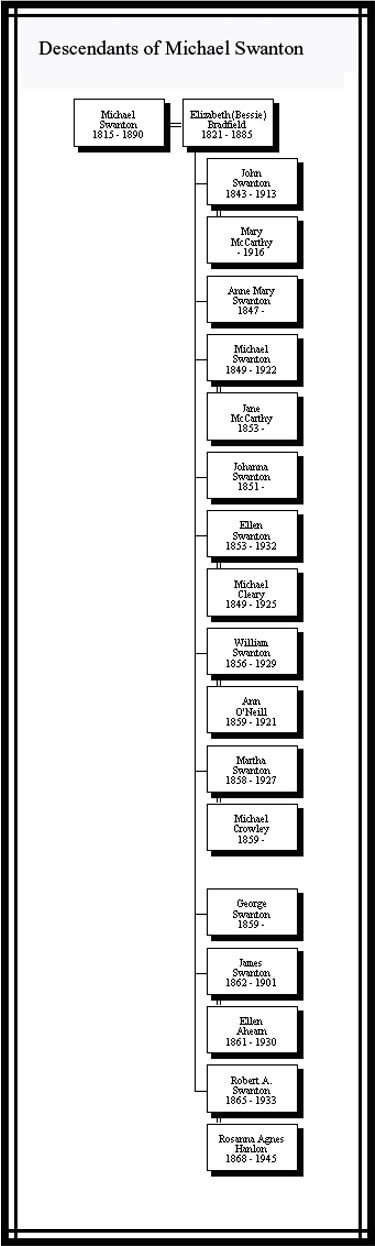

Over a 21-year period, Michael and Bessie had ten children:

Parish baptismal records don’t include the name of the townland where the family lived. Robert was Michael and Bessie’s tenth and last child,, and the only one who was born after 1864, which is when civil registration became mandatory. His civil birth record confirms that the family was living in Boulteen at the time of his birth (April 24, 1865).

Michael and Bessie and their family survived the potato famine of 1845-1847, although it appears that they didn’t have any children in 1845 or 1846.

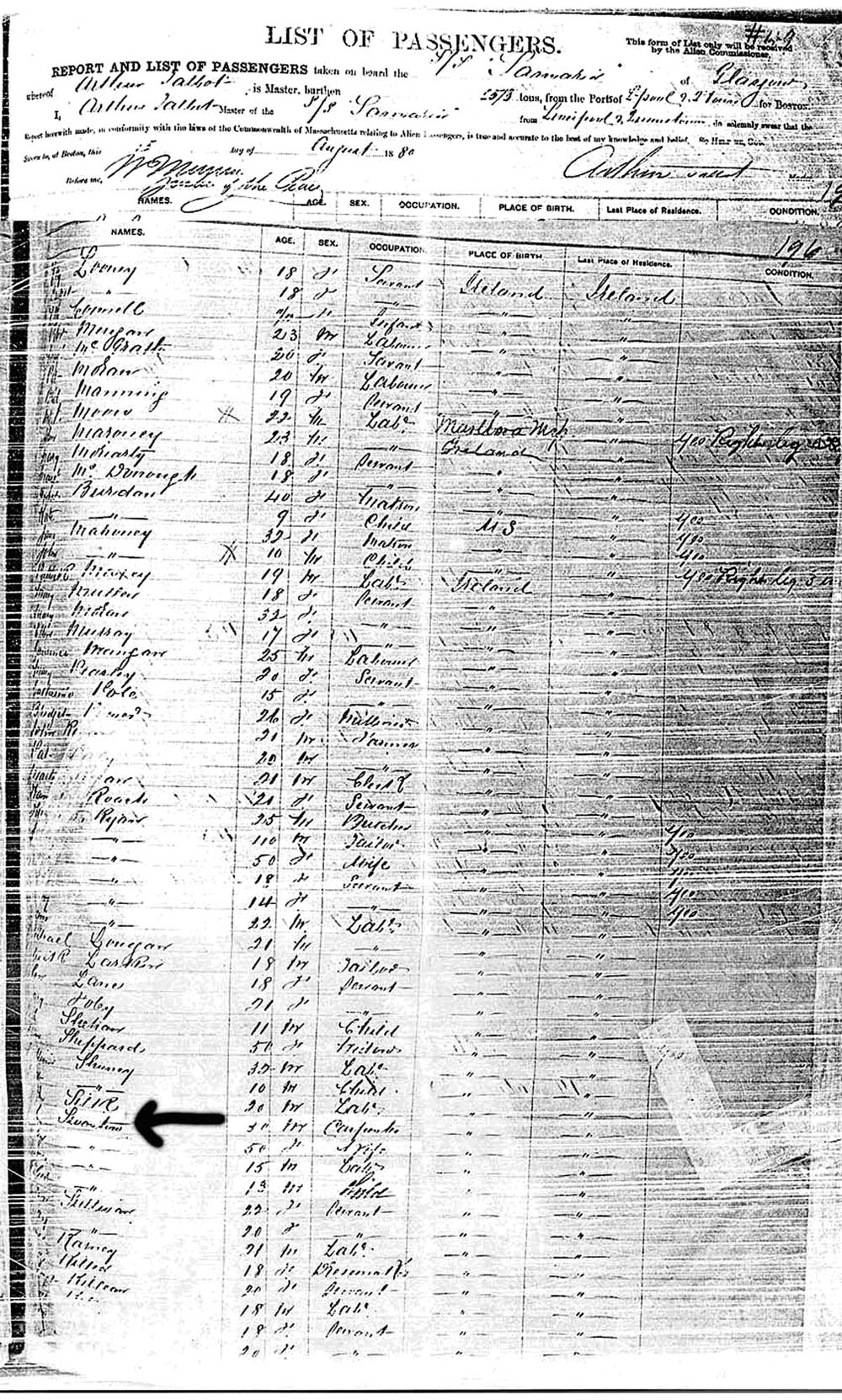

In August of 1880, Michael, Bessie, and their sons James and Robert, left Ireland, immigrating to Boston, Massachusetts. Michael would have been 65 and Bessie about 60 years old then.

I wondered why Michael and Bessie decided to emigrate after they had spent most of their lives in Ireland. I found a number of newspaper articles that appeared in the West Carbery Eagle between January 10,1880 and March 13, 1880 that painted a grim picture of the dire conditions that existed in the united parishes of Enniskeane, Kinneigh, and Desertserges. It is very likely that Michael and Bessie Swanton were among those who attended the meeting held at the Enniskeane Church on January 31,1880.

In light of the desperate conditions that existed in the Castletown-Kinneigh and surrounding areas in 1880, it isn’t surprising that Michael and Bessie Swanton decided to leave Ireland and to immigrate to the United States. It also isn’t surprising that their son, Robert, who was my great-grandfather, never talked about his life in Ireland to any of his family. The only thing he ever told his family was that “he was born by the bridge.” Perhaps this bridge spanning the Bandon River near Enniskeane was the one to which he was referring.

It was very common in those times for Irish immigrants to join family members who had already emigrated and who were settled in their new homes.

George W. Potter observes the following in his book To the Golden Door: The Story of the Irish in Ireland and America:

Michael and Bessie’s son, John Swanton and his wife, Mary McCarthy Swanton, had immigrated to Boston in 1873, and had settled in South Boston, Massachusetts.

Making the decision to leave their homeland of more than 60 years probably wasn’t easy for Michael and Bessie, in spite of the hardships they had endured there. They were leaving behind a lifetime of friends, memories, and a way of life that their families had followed for generations.

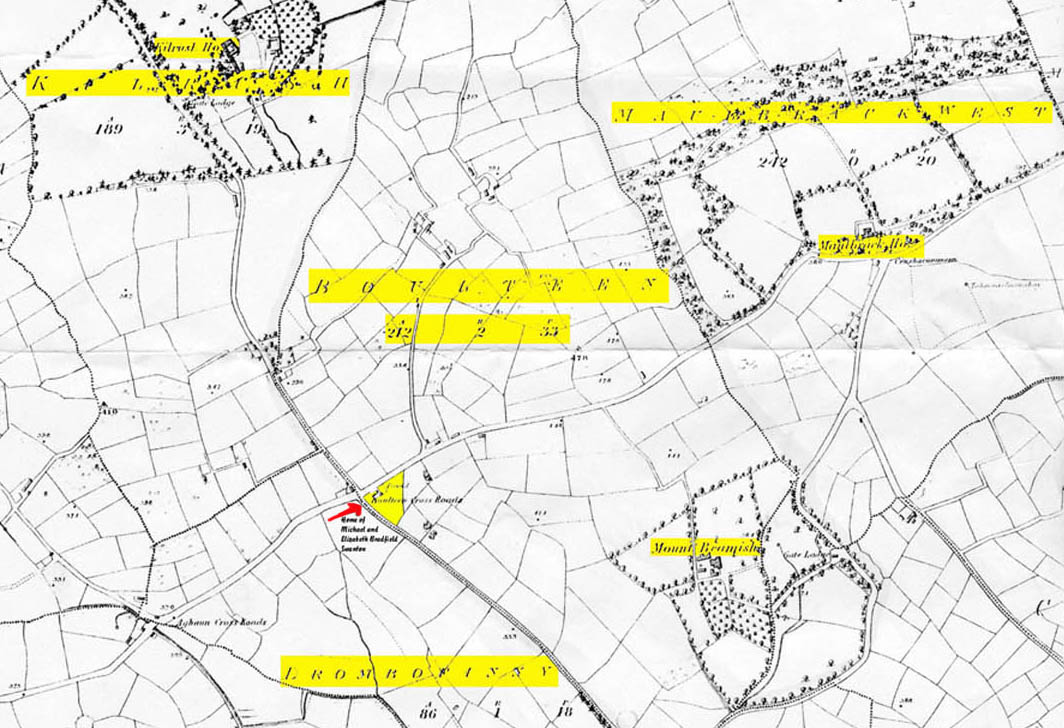

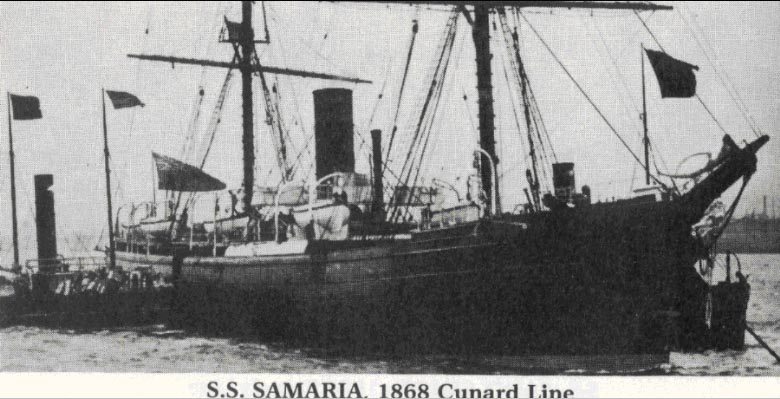

Nevertheless, Michael and Bessie sold their household furnishings, packed up their meager possessions, and in August of 1880, they departed from the port of Cobh , County Cork, on the S. S. Samaria with their sons James, age 18 and Robert, age 15, bound for Liverpool and eventually Boston, where they arrived on August 15.

The S. S. Samaria was built in 1868 by J. & G. Thomson, Ltd., Clydebank, Glasgow, Scotland, and was part of the Cunard Line. It weighed 2,605 tons, and was 320’ long and 39’ wide. Propelled by a single screw, it traveled at 12 knots an hour. It had two masts and one funnel, and an iron hull. It could accommodate 130 cabin passengers and 800 third class passengers. Michael, Bessie, Robert and James traveled in third class. The journey would probably have taken up to two weeks, depending upon the sea conditions. The S. S. Samaria was scrapped in 1902.

Although Michael was 65 and Bessie when 60 when they emigrated to Boston, both of their ages were recorded as 50 on the Samaria’s passenger list, and James’ and Robert’s ages were recorded as 15 and 13, although they were actually 18 and 15. There is quite a bit of disparity in the ages my Irish ancestors provided for various records. It’s possible that they didn’t remember exactly when they were born, or they simply didn’t care. Another theory is that they might have represented themselves as younger on the passenger list in order to ensure passage. A 50-year old man would have been perceived as more able to find a job in the United States than a 65-year old man.

Although the Irish had been immigrating to Boston since before the potato famine, it had been at a slow enough rate that they could easily be accepted and assimilated into the area. During the potato famine, thousands of Irish immigrants poured into Boston, and their sheer volume made it very difficult for them to be assimilated. Many of the Irish who arrived in Boston during the famine years were ill, destitute, and unable to work. Large families crowded together into wooden-frame tenements with inadequate sanitary facilities and ventilation.

The Irish were regarded as drunkards and brawlers, and were not welcomed by the locals, who reputedly hung “Irish Need Not Apply” signs in their store windows. Saloons sprang up on every street corner, and they provided a place for the Irish men to get together and enjoy the company of their fellow countrymen.

Often, Irish families were supported by their women, who hired themselves out as domestics, while the men tried to find day labor.

By 1880, the flood of immigration into Boston had diminished. The Irish were carving out a niche for themselves in their new home, and were slowly becoming assimilated and accepted. Ambitious Irishmen had risen up from menial jobs and were now successful real-estate investors and contractors. The Irish were also becoming involved in politics, and in 1884, Boston elected its first Irish mayor.

Although by 1880, attitudes in Boston were more favorable toward the Irish, the Irish still tended to live together in close-knit communities, carrying on their religion and traditions, and raising their children as their parents had raised them.

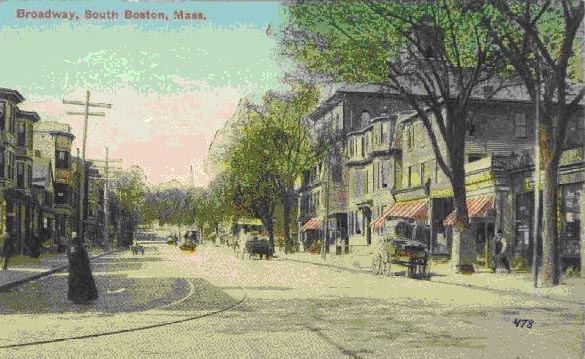

South Boston at the Turn of the Century

The following excerpt from the book South Boston: My Home Town by Thomas H. O’Connor, paints a colorful and evocative picture of South Boston before the turn of the century.

Michael, Bessie, Robert and James arrived in Boston in August 1880, just after the census had been taken. This may have been deliberate timing on their part, as many of the Irish were reluctant to answer the questions the census takers asked. Their position in their new home was very tenuous, and they may have felt that the less people knew about them, the better.

Michael, Bessie, Robert and James would have been greeted at the dock by John, Mary, and their children. Their first night in Boston would have been a time of rejoicing and celebration, with simple, but ample, food and drink. It had been more than 6 years since Michael and Bessie had seen their son John, his wife, and their grandchildren.

This was the also first time that Michael and Bessie met their three granddaughters, who had all been born in Boston. The oldest girl, Elizabeth, was 4 years old and had been named after her grandmother. The next granddaughter was Catharine, who was 2, and little Mary, who was nine months old. The boys had been born in Ireland, before John and Mary had emigrated, and James was 8 and John was 6.

Michael and Bessie moved in with John, Mary, and their five children. They lived at 306 West Second Street in South Boston, Massachusetts, a predominantly Irish community. They lived in a 2-family house, and with the new arrivals, the Swanton household was now comprised of twelve people. Another seven lived in the McDonald household in the same house, bringing the total number of the inhabitants of the house up to 19.

In 1882, three more of Michael and Bessie’s children immigrated to Boston. William arrived at the Port of New York on May 1,1882, and it is very likely that his sisters Ellen and Martha came over with him, as they both also arrived around the same timeframe. William didn’t move in with his already crowded brother, John. Instead, he lived on South Street in Boston.

Sometime before 1883, John Swanton, his family, and his parents and brothers, moved down the street to 274 West Second, which presumably had more room to accommodate them all. Ellen Swanton and Martha Swanton may have moved into the house at 306 West Second then, as Ellen, her husband and their children still lived there in 1898.

In 1883 and 1884, Bessie and Michael celebrated the marriages of three of their children. On February 6, 1883, Martha Swanton was married to Michael Crowley; September 30, 1884 Ellen Swanton was married to Michael Cleary, and on October 5, 1884, William Swanton was married to Anne O’Neill.

Bessie Bradfield Swanton died on Sunday, June 28,1885 at her home at 274 W. Second St., South Boston of heart disease at the age of 65, just five years after she left Ireland. Her funeral was held on Tuesday, June 30,1885, with a high mass at St. Vincent’s Church in South Boston.

Bessie died just one month before Ellen Swanton Cleary’s first child, Margaret Cleary, was born, and two months before her son James Swanton married Ellen Ahearn.

Five months later, her granddaughter, little Margaret Cleary died, and she was buried with her grandmother in Old Calvary Cemetery. In 1887, Elizabeth Crowley, just a year old and the first child of Martha and Michael Crowley was also buried there, and in 1898, Elizabeth’s 4-year old brother, John Crowley, joined them in this grave.

In 1921, Annie Swanton, the wife of William Swanton, Bessie’s son, was buried in the same grave as Elizabeth Bradfield Swanton. William had a stone engraved with the names of his mother and his wife. Although Bessie had died in 1885, the year 1884 was erroneously carved on her gravestone.

After Bessie’s death, Michael had no reason to remain in Boston. Most of his children were married now and they were busy raising their own families. I've always gotten the feeling that Michael's children weren't very close to him and perhaps didn't think very highly of him. I got the impression that Michael might have been over-fond of the drink (his sons Robert and William both were, according to Robert’s daughter and William’s neighbors in Lislevane). My great-aunt Mary (Robert’s daughter) remembers they had a cat named Mike, which suggests other tendencies, too. Robert didn’t name any of his sons Michael. So I just have the general impression that he wasn’t very close to his family, or that there was some kind of problem there...

Anyhow, for whatever reason, after the death of Bessie, Michael Swanton decided to return to Ireland.

When Michael and Bessie had left Ireland in 1880, their son, Michael, and his wife, Jane McCarthy Swanton, moved into their old home in Boulteen, County Cork. Michael and Jane lived there on May 1,1884, when their son, James, was born. There are no records indicating where Michael Swanton Sr. lived when he returned to Ireland after Bessie’s death. Perhaps he went back to live with Michael and Jane, although it was about this time that Michael and Jane immigrated to New York.

I haven’t been able to find any more information about Michael and Bessie’s other children, Anne, George and Johanna. They may have remained in Ireland, and perhaps Michael stayed with one of them when he returned to Ireland

Michael Swanton Sr. had been plagued with health problems since 1880, suffering from stricture of the urethra. On August 17,1890, he died at the age of 75 after a 2 month-long bout with urinary fever, doubtless contributed to by his chronic condition. Michael died in the Bandon workhouse.

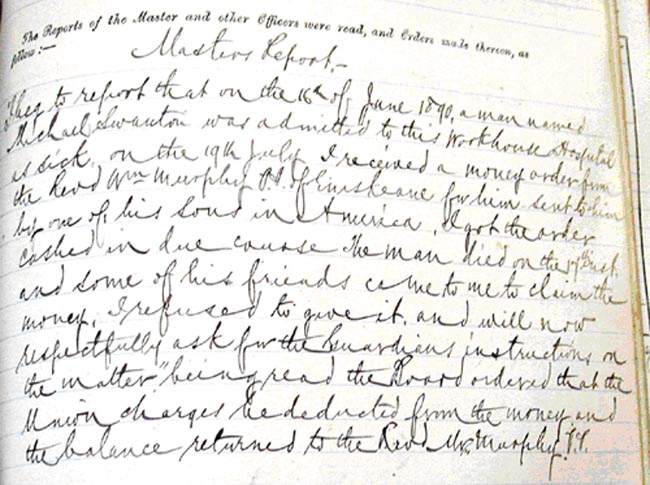

The workhouses had been Ireland’s poorhouses during the famine years, but in later years, they were used as homes for the sick and elderly. I couldn’t help but wonder, though, why Michael’s children didn’t take care of him during his last illness, but left him to die alone and forgotten in the workhouse, and to be presumably buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave. This always bothered me, but in 2001, during a trip to Ireland, I finally came across the answer to this puzzle in an entry from the minutes of the guardians of the Bandon workhouse.

Finding this information made me feel a lot better. Now I knew that Michael had not been abandoned and forgotten by his family. It was probably Michael’s son, William, who had sent the money, as he was the only one in the family who had any. This also let me know that Michael had some friends in the workhouse, although they seem to have been far too interested in acquiring the money William had sent for Michael’s care.

A couple of questions remain: did Father Murphy use the remaining money to give Michael Swanton a proper Catholic Mass and burial, and if so, where was Michael buried? Perhaps someday I’ll be able to learn the answers to these questions.